Safenet Deep Dive

I recently got a chance to meet the Safe team at Devcon to chat about their new product Safenet, which was just announced this week.

High-Level Overview

The last few years have brought us an explosion of new blockchains. This has helped with scaling, but brought about new challenges. If you have funds on one chain, but you want to interact with an application on a different chain, there’s a long and arduous set of steps required to move your funds across the chains and achieve your goal.

There has been a lot of effort recently to abstract this complexity for users. The general idea is that users should only need to specify an “intent”. This intent describes what the user is trying to do, and abstracts the specific transactions that are needed to get there. The long-term vision of intents is that users should be able to operate across multiple chains so smoothly that it feels like it’s all one system.

Early efforts to facilitate intents were high-cost, high-latency, or required centralized trust (more on that below).

Safenet enables low-cost, low-latency intents without centralized trust assumptions.

Detailed Problem Description

The easiest way to understand Safenet is by looking at a specific problem.

Imagine I have some USDC on Optimism. I would like to swap some of it for 1 ETH on Base.

Until recently, I had two options:

The Decentralized Path: Move the funds through a series of trust-minimized bridges and swaps. For example:

- Bridge the USDC to Ethereum using the Optimism native bridge.

- Bridge the USDC to Base using the Base native bridge.

- Swap the USDC for ETH using Uniswap.

There are several disadvantages to this method:

- The process is tedious. You have to sign a series of transactions. Services like Li.fi are designed to help with this. You can pre-sign the transactions and they’ll babysit the process for you for a small fee.

- The process is slow. The funds must flow through a series of sequential transactions across multiple chains.

- Costs are high due to the number of blockchain transactions (especially if the transaction needs to flow through Ethereum).

- You must correctly predict gas costs and swap rates as you’re planning the flow. In the best case, you have some leftover funds on the destination chain. In the worst case, you underestimate costs and your plan stalls mid-way through the flow, which leaves you with an asset you don’t want on a chain you don’t want.

The Centralized Path: Send the USDC to a centralized “processor” who promises to fulfill the intent. Here is a snippet from Rhino.fi bridge docs:

As mentioned, the bridging process involves the user giving rhino.fi assets on their origin chain and rhino.fi providing their desired assets on their destination chain. In other words, the user gives us tokens and trusts that we will give them tokens on another chain.

This gives you:

- More Speed: The centralized processor can deliver your funds immediately after they receive your send. They don’t need to find a decentralized path of bridges/swaps to the destination.

- Lower Cost: The centralized processor can leverage off-chain liquidity. This can be especially cost-effective for assets where the on-chain liquidity pools are small.

The tradeoff is that you must send your funds to a central authority, and hope they deliver what you asked.

The Solution

Safenet aims to provide the best of both worlds. Users should be able to leverage the speed and pricing of the centralized processor, without centralized trust assumptions.

Let’s walk through how Safenet handles the operation I described above.

I have some USDC on Optimism. I want 1 ETH on Base. To optimize speed and cost, I would like a centralized processor (like maybe a centralized exchange) to facilitate the transaction, but without the trust assumptions typically associated with a centralized exchange.

Safenet refers to the source chain (Optimism in our case) as the “debit chain”, and the destination chain (Base in our case) as the “spend chain”. I’ll use those terms here.

Prerequisites

Before using Safenet, I’ll need to create a Safenet account. This creation will do a few things:

- It will deploy a smart contract wallet on both the debit and spend chain.

- It will configure these accounts to enforce that all spending transactions from the wallet must be co-signed by the processor (in this case, the centralized exchange). (more on this later)

Also, I’ll need to fund the wallet on the debit chain.

Once the wallets are deployed and configured, I’m ready to use Safenet.

Using Safenet

Step 1: I go to the website of the centralized processor. The processor says I can swap 1 ETH on Base for 3500 USDC on Optimism (They calculate this offer based on the market price of ETH + some fees for processing).

Step 2: I create an off-chain “intent” (Safenet calls these transactions) by signing a message and sending it to Safenet’s off-chain transaction pool. This intent denotes my expectations. I expect 1 ETH on Base, and I’m willing to trade 3500 USDC on Optimism.

Step 3: The processor sees the transaction and pulls it from the pool.

Remember that the smart contract wallet is configured such that the processor must co-sign any spends from the wallet. This allows the processor to “lock” the funds.

The arrow shown in the above diagram does not represent an actual transaction on-chain. The lock is managed by the processor. If I try to create a transaction which would bring my balance below 3500 USDC, the processor will refuse to co-sign that transaction. This effectively locks 3500 USDC in the account. This method of locking is key to Safenet’s speed (creating the lock on-chain would require waiting for transactions to finalize).

You may be wondering, “If the processor must co-sign all spends, what’s to stop the processor from refusing to co-sign any transactions and holding my account hostage?” I’ll explain the solution for that later.

Step 4: The processor delivers the 1 ETH to my account on Base, fulfilling the intent.

Step 5: The processor notifies the smart contract wallet on the debit chain (Optimism) that an intent was fulfilled. The smart contract wallet verifies the intent was signed by me.

At this point, the processor has notified the debit chain that the fulfillment is complete, but has not provided any proof. Verifying the fulfillment is very easy to do off-chain, but slow and expensive to do on-chain. Instead of providing the proof on-chain, the processor makes an on-chain claim that the intent is fulfilled (without providing any proof). The processor adds some collateral with this claim, which essentially says “If I’m lyin’, I’m dyin’”. If the processor is shown to be lying, they will lose the collateral (more on that later).

Step 6: A challenge period ensues, during which time, the claim can be disputed. If there are no challenges during the period, the smart contract wallet will allow the processor to withdraw the locked funds at the end of the period.

Claim Disputes

As mentioned, it’s easy to verify off-chain that an order was fulfilled. If the processor is lying, anyone can easily detect this and issue a challenge on-chain during the challenge period. By issuing the challenge, the validator is accusing the processor of lying. Validators are incentivized to challenge false claims. A validator who challenges a false claim will receive the processor’s collateral if the validator is shown to be correct. It’s important to note that the validator must also put up collateral to issue the challenge.

When a claim is challenged, it means either:

- The processor is lying (the processor claimed the intent was fulfilled when it was not)

- The validator is lying (the validator claimed the intent was not fulfilled, but it was).

At this point, the processor must undergo the long and expensive process to prove on-chain that the funds were delivered. It’s important to note that both parties involved in the challenge have to put up collateral, and whichever party is ultimately shown to be lying will lose their collateral to the party that is not lying. In practice, this means it doesn’t pay for either party to lie. Because lying doesn’t pay, these challenges should be very rare.

Generalizing The Problem

Now imagine I have USDC on Optimism, but instead of wanting ETH on Base, what if I wanted to stake MATIC on Polygon, or purchase an NFT on Avalanche?

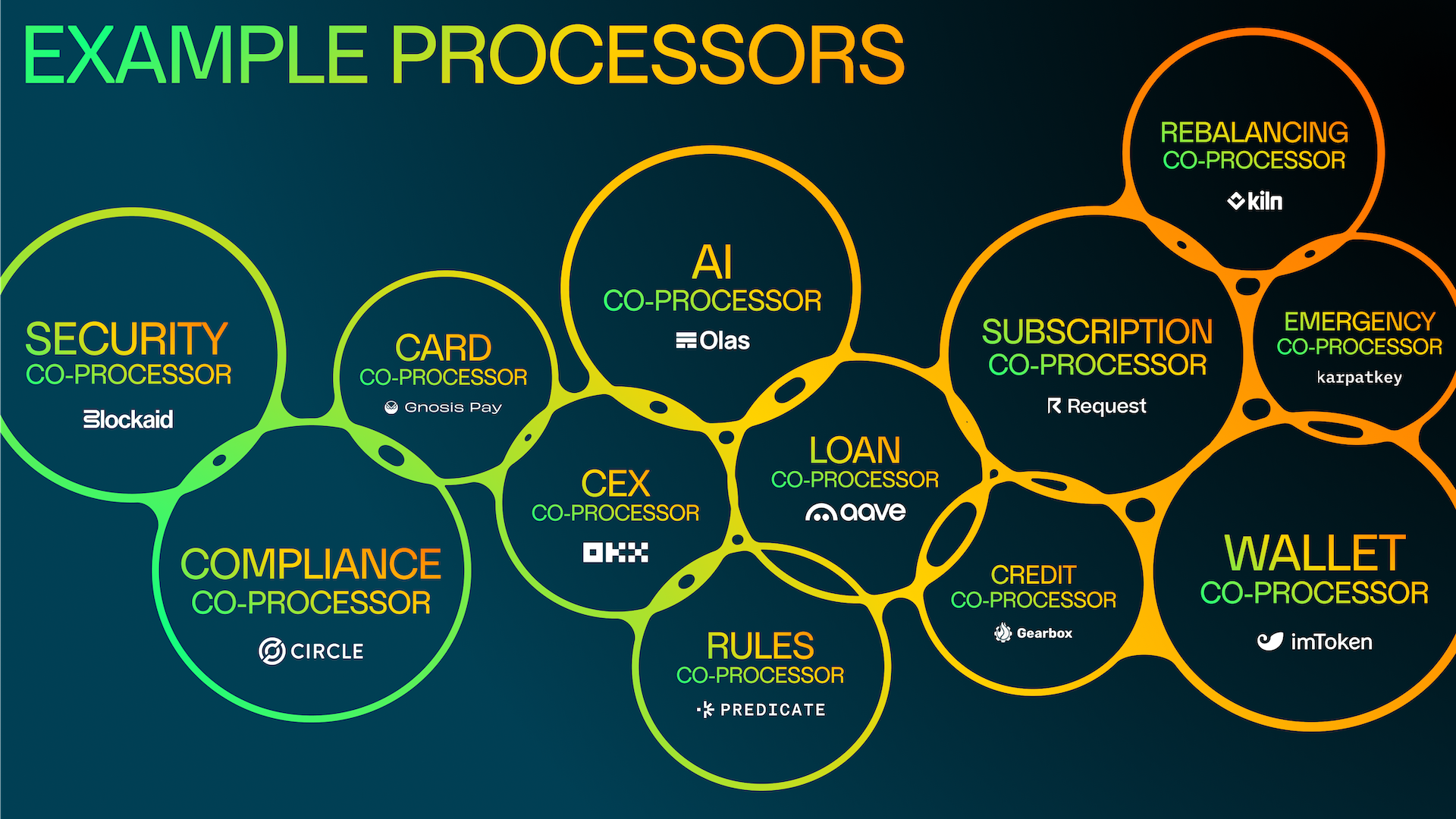

There are an unlimited number of things I might want to do, and each type of intent requires specialized logic to fulfill that intent. Safe envisions that specialized processors will fulfill specific types of intents. They call these application-specific processors.

We can picture how the original intent described in this post could be fulfilled by the OKX co-processor (OKX is a centralized exchange who can leverage their liquidity to fulfill this intent).

Additional Benefits To Processor

Aside from trust benefits to users, this architecture is helpful to processors.

The resource lock in the smart contract wallet works somewhat like an escrow. Without this escrow, the centralized processor must receive funds from the user, and then subsequently deliver the desired tokens on the destination chain. During the period of time after the processor receives the funds, but before the funds have been sent to the destination chain, the processor is holding funds which belong to the user. Holding user funds exposes the business to a large set of regulatory concerns (“safeguarding” for example).

Because of the escrow, in the Safenet protocol, the processor never takes custody of the user’s funds. They don’t receive a payment until after they’ve delivered their promise to the user. In this case, the processor never holds funds which belong to the user. This alleviates a large class of regulatory concerns.

An Intents Marketplace

In the flow I described, the user expects a specific processor to fulfill their intent. In future versions of the protocol, this won’t be required. Users will be able to create processor-agnostic intents on-chain. Processors will bid to fulfill the intent, and the processor with the winning bid will get the job. This creates a Google-Ads-like marketplace which increases competition between processors and results in better pricing for users.

You may be wondering: “If locks are enforced by ensuring a specific processor co-signs all transactions for the wallet, how can the wallet interact with multiple processors?” In reality, the wallet will continue to have a single “processor” who is co-signs transactions, but that processor will only be responsible for managing the lock. The actual intent fulfillment will be done by third parties (co-processors) who compete in the marketplace on pricing and speed. These co-processors must trust the processor to manage the lock properly. If the processor were to sign a transaction which violates a lock, the co-processor would not be able to redeem the escrowed funds.

Risks

Let’s take a look at the different actors in the system and analyze potential risks.

Risks For The Processor

Processor Pricing Risk & Opportunity Cost

After the processor delivers the asset on the spend chain, they are entitled to withdraw the asset on the debit chain, but not until the challenge period is complete. From the processor’s perspective, there are two downsides to this delay.

- These funds cannot be used to fulfill more intents until the challenge period is over.

- During the challenge period, the processor is exposed to fluctuations in price of the locked asset.

These two factors may have some impact on transaction cost (compared to skipping Safenet and using the centralized processor directly with trust).

The protocol allows the processor to extract the funds on the debit chain at any time if they prove on the debit chain that the funds were delivered. However, as described previously, most proving methods currently tend to be expensive and time-consuming, and so waiting for the withdrawal period is more economical in practice.

Processor Unable To Collect Funds On The Debit Chain

A set of attackers who control 51% of the debit chain could potentially revert the transaction which funded the safe wallet, which would prevent the processor from collecting the funds. An attack like this is very difficult to orchestrate on most chains.

Risks For The End User

False Proofs

To resolve disputes, the truth must be propagated from the spend chain to the debit chain (to prove the intent was fulfilled). There are many ways to facilitate the propagation of that data. Between some chains (like Ethereum and Optimism), data can be propagated by trust-minimized bridges. In other cases, oracles may be required to propagate the data.

The various methods come with different trust assumptions. For example, if oracles are required, a malicious processor controlling 51% of the oracles could generate a false proof that the funds were delivered, and propagate that data to the debit chain. This would allow the processor to steal the user’s funds, and steal the collateral from the validator.

Safenet’s protocol doesn’t prescribe any specific proving method. Safenet has a pluggable architecture which can support many different types of proofs.

At its core, Safenet is simply a way to pull funds from an account using 'proofs.'

— lukasschor.eth (@SchorLukas) December 8, 2024

It is agnostic about the type of proofs (fraud / zk), how it is sourced (message bridge / off-chain oracle), and what it proves (optimistic cross-chain tx, trade on Binance, scheduled tx, etc.).

In Safenet, each intent specifies the proving mechanism that will resolve disputes for that intent. The Safenet protocol doesn’t prescribe any specific proving methods for intents, and so the protocol itself does not guarantee the safety or validity of proofs. Users who create intents must understand the proving method defined on that intent, and the trust assumptions that come along with that proving method.

Processor Holds The Funds Hostage

Imagine the processor tries to permanently freeze the user’s smart-wallet by refusing to co-sign any transactions.

In this case, the user can initiate a withdrawal without a co-signer. A wait period will be enforced before the user is allowed to withdraw the funds. This wait period ensures that any pending intents finish before the user withdraws.

How Does Safenet Compare To Other Cross-Chain Intent Protocols?

Across protocol is another protocol designed to facilitate low-latency, low-cost intents without centralized trust assumptions

UniswapX also recently announced a new protocol called “The Compact”.

chain abstraction is all the rage right now

— 0age (@z0age) November 26, 2024

value transfer across chains must become totally seamless

this is the vision for cross-chain UniswapX

been building out one of the primitives to help get there — a new protocol for reusable resource locks:

The Compact 🤝

let's 🧵

Safenet and The Compact use very similar algorithms. The most noticeable distinction between them is that Safenet escrows funds in a user’s smart contract wallet, whereas in The Compact protocol, user funds are held in a standard smart contract and escrowed there (the protocol makes an explicit choice to be unopinionated about wallets). The Safe team are experts in smart contract wallets, which makes them uniquely suited to building a smart contract wallet based approach.

What Are The Benefits Of Escrowing The Funds In The Smart Contract Wallet?

The in-wallet escrow provides some clear UX benefits:

- Users can treat their Safenet wallet as their primary spending wallet, using it even for non-Safenet transactions (like buying an NFT on OpenSea). One caveat is that the processor must co-sign all spending transactions from this wallet. If the processor experiences an outage, all funds will be frozen until the processor comes back up (or the user goes through the non-co-signed withdrawal flow).

- Users can see all their Safenet funds using a normal wallet app. While it is also possible for a wallet app to display the funds in an external smart contract, gathering the data is complex because your wallet must locate the external accounts.

- Users don’t have to remember to pull excess funds back into their wallet (the funds never leave your wallet until they are redeemed by the processor).

From a security perspective, while it certainly feels safer to keep the funds in your wallet, the risk is theoretically the same in both approaches. At the end of the day, there’s a smart contract which manages the escrow, and your ability to get those funds back is dictated by the logic of that smart contract.

Coupling the protocol to smart contract wallets could also be limiting in some ways. Extending these protocols beyond EVM is already difficult, and coupling the protocol to smart contract wallets adds some more complexity when expanding beyond EVM (every chain needs smart contract wallets that support the Safenet primitives).

The decision to leverage smart contract wallets also means that the success of Safenet hinges on the adoption of smart contract wallets. The long-term prospects of smart contract wallets look good. The Ethereum ecosystem plans to move completely to smart contract wallets in the future. However, most users today still transact on-chain using traditional wallets, which could create some early barriers to adoption. EIP-7702 aims to reduce the barrier to entry for smart contract wallets, but unfortunately, EIP-7702 wallets cannot be used with Safenet and will not help with adoption in this case.

EIP-7702 wallets have an admin key (owned by the user) which has god-like permissions on the wallet. These permissions would allow the user to extract the locked funds.